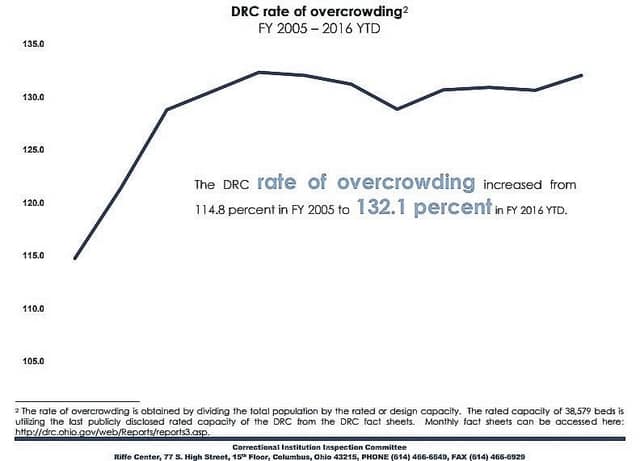

The criminal justice system can’t handle the surge of women incarcerated for drug-related crimes. With populations rising of inmates incarcerated for low-level non-violent drug crimes, there has been a 700 percent increase in the number of women incarcerated since 1980. More than one-third of all women behind bars are there for drug-related crimes.

The resultant overcrowding inside jails—today blame is placed on the heroin/opioid epidemic, in past years mandatory sentences for minor marijuana possession was blamed for institutional overcrowding of inmates—has caused outbreaks of disease, repeated state inspection violations and unsanitary conditions that create safety risks for the inmates living behind bars.

Such is the case in the Fayette County Jail.

Opioid and heroin users are regularly booked into the Fayette County Jail. If a user overdosed and the medics were called, the police respond and locate the syringe and any other paraphernalia and drugs. The person who overdosed is charged with a felony for possession of drugs or possession of drug abuse instruments.

As they sit in jail and await pre-trial services and arraignment, the inmates who are addicted to opioids and heroin begin the slow, painful withdrawal process.

Some inmates sit in the jail’s drunk tank: a cell lined with concrete benches with a drain in the middle for the physically sick. Severe symptoms can last up to three days and can include nausea, vomiting, chest pain, difficulty breathing, psychological troubles and coma. Once they’re physically able, the inmates appear in court, at which point the judge may decide to send them back to jail without release until they can be sentenced to a drug treatment center.

When drug offenders are released—after spending days or weeks in jail withdrawing and detoxing the drugs out of their systems— they hit the streets to score more drugs, but with their tolerance for the drugs now lowered, it could cause another overdose, leading them back into jail. And sometimes, if they don’t overdose on the street, they risk an overdose in jail, as contraband being conveyed into the jail has been a “huge problem,” said the deputies who work in the jail.

Tiara L. Adams was booked into the Fayette County Jail June 3 following an indictment for possession and trafficking of heroin. She was taken by squad to the Fayette County Memorial Hospital five days later and treated for an overdose; law enforcement officials said narcotics had been smuggled into the jail, leading to Adams’s overdose. She was brought back to the jail, separated from the other inmates, and left in the booking room with the lights off, according to deputies. They thought she was sleeping—yet eventually realized she was non-responsive and was taken to a medical center in Columbus, where the 22-year-old mother died two days later. Adams’s family declined to speak to the Record-Herald.

Drug treatment within the county itself is limited and transitional sober housing doesn’t exist for those trying to get out of the cycle of addiction and institutionalization. In return the jail has become the sober living house for the county’s low-level, non-violent drug offenders.

Inmates may spend weeks or even months sitting in the jail waiting to be sentenced to a drug treatment facility. Drug treatment centers in the state have waiting lists, but centers in Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton (each about an hour’s drive from Fayette County) provide hopeful options for drug offenders.

The Fayette County Jail has the capacity for 50 beds but population has spiked to over 80 inmates, with the average population around 64 inmates per day in 2016, according to statistics provided by Andy Bivens, chief deputy at the Fayette County Sheriff’s Office. On average, the number of women in the jail comprise about one-third of the jail’s daily population.

Women between the ages of 25 and 29 have the fastest growing incarceration rate in the state. Forty-two percent of all women incarcerated in Ohio between the ages of 25 and 34 were incarcerated on drug-related offenses in 2016.

As a growing number of women cycle through addiction, poverty, homelessness, treatment, probation and supervision, and jail, their time in jail may be one of their only opportunities for sober living.

For 35-year-old Annette E. Burris, the Fayette County Jail is her sober home. Burris moved to Fayette County when she was 6-years-old. She has been in the Fayette County Jail 39 times and at the time of this interview had been in the jail for 42 days waiting to get into a treatment center.

Burris said all her stints in jail have been alcohol and drug-related.

“When I get drunk I will do just about anything that gets put in front of me, so, I’ve had one possession of heroin charge that was just for residue,” Burris said.

Things have gotten bad over the years. Her drinking began at age 13 when her father committed suicide. In between her time in jail, she lost her mother, kids, spouse, home, vehicle and job.

This time she was placed in the jail after overdosing on heroin and being revived by medics.

“I don’t normally do heroin. I was drunk as a monkey, I went to a friend’s house and they had like a little tiny line of heroin, and they had to send two squads,” Burris said.

Years ago Burris had a prescription for Xanax and Vicodin, but she doesn’t attribute the prescription pills to her gateway into alcohol and drug dependency.

“I have a family history of alcohol and drug abuse. My mother passed away of hepatic (liver) failure just a couple years ago. It goes back generations on both sides of my family. I am a genetic alcoholic as well as I have learned through behavior,” said Burris.

Addiction experts emphasize that addiction is not genetic. There is no gene or character trait associated with addiction, said Brad Lander, an addiction medicine specialist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. He says that addiction comes solely from learned behavior.

“As people get into addiction and get addicted, they get more alike,” said Lander, which explains why people in the same family have similar patterns of addiction.

So far Burris has been to six different residential treatment programs. The last treatment center she lived in was in Dayton, where she completed a program for cognitive behavioral therapy.

“I passed with flying colors,” said Burris. “When I came home, I got a job within a couple days.”

She said she believes drug and alcohol treatment works, but, she said, “The problem I see a lot in Fayette County is right now, I had to go to prison for my heroin possession charge, when I got out, there was really nowhere for me to go in Fayette County. When I get let out of jail this time I’m going to be right back on the street.”

Burris always relies on family and friends for a place to live. All of them are drug and alcohol users.

“The thing is, family members are still using. After about three months of…constantly being around alcohol and drugs, one thing led to another…and I got addicted.”

As the jail now acts as the warehouse for women’s sober living, Burris said the county needs to start sober living housing programs for people who have completed treatment. This would give the hundreds of people in the county who are transitioning back into society a means to obtain sober living rather than going back into the familiar patterns of addiction among friends and family that lead them to jail time and time again.

Today there are two rooms full of women in the Fayette County Jail. When Burris first started coming to the jail, women were housed in a single four-man cell.

“I’ve seen 24 women in a 12-man cell. We’ve had seven women on the floor in here since I’ve been here. This is the most I’ve ever seen. And like I said, I’ve been coming here for quite some time,” said Burris.

Sgt. Matthew Weidman of the Fayette County Sheriff’s Office is the jail administrator. He has seen the number of women in the Fayette County Jail skyrocket due to drug-related offenses. Weidman recalled that when he began working at the jail 20 years ago, there may have been a handful of women in the jail, five at the most. In 2016, the jail saw an average of about 19 women per day.

Weidman admittedly has a hard time managing the overcrowded women in the jail. He said it’s a complicated situation and that the women are sometimes not able to take care of themselves because of the drugs and withdrawal symptoms.

Then there have been cases of parasitic disease, what Weidman said was a “big thing of head lice” that confirmed their feelings that they can’t handle the unsanitary conditions created by the overcrowding of women inmates.

Jails with physical space limitations and inadequately trained staff are not only non-compliant to state jail standards but tend to have higher incident and misconduct rates, according to the Bureau of Adult Detention. The bureau cites correlations among staff training of administrators and supervisors to the overall jail security and incidences of contraband.

Without criminal and social justice reform for non-violent, low-level drug offenders who are incarcerated, overcrowded conditions will persist in jails alongside the rise in drug charges for possession and drug paraphernalia common in everyday overdoses.

For people like Burris, the jail simply becomes a transient sober home among treatment centers and the street. For drug offenders, probation and supervisory sanctions offer an alternative to going to jail, but these sanctions increase the number of people re-entering jails and prisons significantly. With 35,000 people under supervision in 2015, Ohio has the fifth highest rate of correctional control in the country, with more people on probation and supervision than states like Texas, New York, Florida, New Jersey and California.

The trend of placing people on probation only gives the court more options for putting the person in jail or prison, according to a 2013 Law and Policy Report from the University of Denver (full document readable at NCBI.) One reason that probation leads to higher incarceration rates is because people put on probation and supervision are never fully rehabilitated. Instead they are “set-up to fail with the implementation of mandatory meetings, home visits, regular drug testing, and program compliance incompatible with the instability of probationers’ everyday lives,” according to the American Correctional Association, as some felons view probation as a more severe punishment than a jail sentence.

Once a drug offender violates felony supervision (for example, fails to report for a scheduled probation meeting or fails a drug test) they appear in court to be sentenced for their original drug offense, and are additionally charged with a probation violation and receive a sentence for that crime, too.

Placing low-level, non-violent drug offenders on probation and supervision to save money on incarceration makes the function of diverting and rehabilitating a prison-bound offender less achievable. But even with the movement between probation, supervision, jail and prison, many people continue to view probation and supervision as a low-cost method of rehabilitating a person as compared to the daily cost of incarceration.

Burris said she wants to stop circling through addiction, probation, jail and prison, but said she and other women will continue returning to the jail until they can find affordable, transitional sober living to get stability after completing treatment.

Despite the overcrowded and unsafe conditions in the jail, Sgt. Weidman remains optimistic. The jail consistently fails state inspections due to overcrowding but he said there’s nothing they can do to fix it until they can build a new jail.

Fayette County elected officials are looking to build a new jail, which would expand the capacity to be able to accommodate the growing number of low-level non-violent drug offenders being incarcerated and possibly provide adequate space for drug treatment classes and programs, which they don’t currently offer.

“We could do more for these programs if we had a new jail. The way our jail is laid out, we don’t have the space and the room for sit-down classes,” said Weidman.

For the inmates who sign-up for one-on-one time with a mental health counselor, they meet in the small closet-sized room used for attorney and client meetings, or in the booking room if it’s available. Scheduled inmate appointments with a doctor are conducted out of an even smaller room in the space beneath a staircase just large enough to fit a single chair and filing cabinet.

The Fayette County Jail is the state’s oldest continuously operated jail, according to Fayette County Sheriff Vernon Stanforth, who said during his 2017 swearing-in ceremony that it’s time for the county to focus on corrections. The jail was built in 1883, at the same time as the Fayette County Court House. The courthouse underwent a multi-million dollar renovation recently; Stanforth said they planned to renovate the current jail until they realized it would cost more than if they started over and built a new one.

The project for the new jail received a nod from the Fayette County Commissioners, who ended 2016 with the promise that they would make it one of their top priorities to secure funding in 2017.

“The jail that we currently operate is overcrowded and there are a lot of things that we can’t do to it to bring it up to today’s standards and needs. Especially with the opiate addiction we are facing, there is no room for treatment there at all,” said commissioner Dan Dean during a December interview.

Fayette County elected officials told Ohio State University students last year that the county would like to build a new jail. The students worked with Fayette County leaders to update the county’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan. Their recommendations were unveiled in the “enVision Fayette County plan” that was presented to county members in December.

The plan highlights immediate, short, medium, and long term goals for the county. Securing funds for a new jail was pegged as a medium-term goal for the Fayette County Commissioners under health and safety, with the purpose being to expand inmate capacity and improve safety for officers and inmates, the report said.

The plan’s immediate and short term recommendations for the commissioners are completing the men’s residential treatment facility in the county, taking an in-depth housing assessment of the county to understand which neighborhoods are experiencing the worst decline and applying for state and federal grants to build moderate to middle income housing.

Within the “enVision Fayette County plan,” it says an Implementation Committee should be made to create accountability for implementing the plan. This committee should be comprised of community members and would meet at a minimum of twice a year to track progress, review the next steps in the plan, and report back to the community.

The plan further states that the Implementation Committee and county officials should provide implementation updates in the Record-Herald, on the county’s website, and on any county social media platform. This should include invitations for the public to take part in the implementation process and to discuss major next steps in implementation.

Commissioner Dean told the Record-Herald in December and again in January that the commissioners had applied for a $500,000 capital safety grant to begin working on a new jail.

In a January meeting, the commissioners said they may move forward with a land study to determine where to build the new jail in the county.

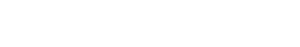

Overcrowding isn’t unique to just Fayette County. The Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections rate of overcrowding increased from 115 percent in 2005 to 132 percent in 2016 when it looked at statistics for all institutions.

Last month, officials in Warren County announced that they plan to move forward in building a new $40 million jail after voters downed a referendum for the jail last May. When an increase in tax was proposed in Hamilton County for building a new jail, it was struck down by opponents who argued that since many of the residents are living in poverty, it placed the burden of paying for the new jail on the shoulders of the poorest tax-payers. The county relies on a mixed combination of institutions to house its inmates in the light of overcrowding low-level, non-violent offenders.

Census data indicates that just over half of the population is employed in Fayette County, with the average income rate of $623 a week, or about $32,000 annually. The county has one of the highest poverty rates in the state, with more than 20 percent of children living in poverty.